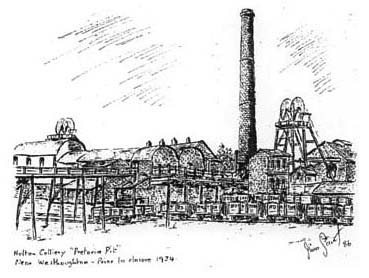

An Account of the Pretoria Pit Disaster 1910 An Account of the Pretoria Pit Disaster 1910

by Jim Sant

The year is 1910, the date 21st December, only a few days before Christmas. Everyone is thinking about the festivities. Presents have been bought, drinks got in and the tree put up.

On this particular Wednesday morning everyone goes to work as usual, in to the mills, workshops and elsewhere. Just before 8.00am, ten minutes to be precise, there is the sound of a dull roar. The floors shake and the sound is heard above the noise of the machines. What's happened? No one knows. Then in comes the over looker, foreman or manager to say "Sorry, but I've got to tell you there's been an explosion at Pretoria Pit. If any of you have relatives working there, get home to find out what's happened and if they're alright".

Most of 'the men and boys working at the pit lived in the areas around Westhoughton, Atherton, Over Hulton and Daubhill. News would filter through perhaps by train to Daubhill Station where the men from that area would have set off from this morning. The line from there used to run past the pit. But imagine the people living on its doorstep. Those in the area of what is now Broadway, off Newbrook Road, lower down than Hulton Park Estate. Around there it must have sounded as though an earthquake had happened. People would run up the path leading to the pit about half to three quarters of a mile from the main road. Before long, a crowd would gather around the pit-head, not knowing whether their husbands, brothers, sweethearts or sons, some of these only boys, would come out alive.

The pit was part of the collieries owned by the Hultons, known as number 3 bank pit. Not a very old one, it consisted of two shafts. These were no 3, or the up cast, sunk in 1900 and no 4, the down cast, sunk in 1901. The shaft were 75 yards apart and the numbers working there at the time were 344 in number three and 545 in number four. There were five coal seems being worked, Trencherbone, Plodder, Yard, Three-quarter and the deepest, the Arley, at 434 yards. The manager Mr Tongue describes the scene when he arrived at the pit-head. "There was smoke coming out of the upcast shaft making it impossible to travel down and the cage was stuck in the downcast."

The Howe Bridge rescue team, from near Leigh, were informed at five past eight and, after getting all their equipment together, they reached the scene thirty-five minutes later at 8.40am.

This was very good indeed. Later they ware highly recommended for their efficiency and speed under the charge of Sergeant Major Hill. At the pit there were five men qualified in the use of rescue equipment, such as breathing apparatus. Only one was available at the time, but during the rescue 148 trained men were used, prior to this disaster, owners and managers of the collieries around the country had been sceptical about rescue teams, for nothing was known about them. The Howe Bridge team proved to be a necessity. So despite the catastrophe of 1910 resulting in a great loss of life, it did prove the value of organised rescues.

It was the first time, according to reports, that a team of men had been used in this way. They cleared the cage from the downcast and made away to get out the entombed men. Those men in the no 4 were all got out, some slightly injured some suffering from fumes, they were the Trencherbone and Arley mines, but the explosion had occurred in the number 3. Only one came out alive, a youth aged 15. He was found with his clothing and hair blown off and lived for a short time when brought to the surface. Another man had a lucky escape. According to the Bolton Evening News the day after the disaster, the man from Churchbank Bolton had got up late. His wife said "Never mind have a day off for the new year it was making up day yesterday". He found out later that day that his workmates had been killed at the coal.

A long and detailed enquiry found out what had caused the explosion. It seems that a large fault traversed the mineral track from east to west and at right angles. This allowed three seams to be worked at one level in the no 3 shaft. These were the Plodder, Three-quarter and the Yard. It was at this level that the explosion had occurred, originating at a point where the men had been working on an existing fall. This was near the farthest intake airway for no 2 face on the north Plodder. A second fall took place, setting free an amount of gas. This in turn, was set alight by a lamp either becoming over heated as it fell through the gas, or by being damaged by a fall of stone. Dust then carried the explosion into the main haulage road and through the rest of the mine in a matter of minutes. This dry dust, which had transmitted the explosion, was stated to be common in Lancashire mines.

Afterwards, a fund was set up to help the widows, orphans and dependent of what was, up to then, the worst tragedy to date in the mining industry. A memorial was erected over the spot where most of the bodies where found. But these do not compensate for the tragic loss hundreds of families in the area endured.

The pit was reopened in 1935, closing in 1960 and some time after this I went round the area trying to find its remains. While walking down the path towards it, I could only think of all the men and boys who had trod the same way on that morning of the 21st December 1910, not knowing what fate waited at the end. It was said that hard, tough miners wept at the scene.

|