Cottontown Biography

by Brian Farris

Do we really remember the warmth and comfort of our mother's arms when we try to recall our earliest memories? A small room in a tiny terraced house with uneven floors flagged with slabs of natural stone. A bare light bulb, such luxury when most had cold noisy gas, lighting a dark pegged rug in front of a shabby but polished brass fender and fireguard with a shiny brass top rail. The black cast iron fire place with a built in water heater and oven, surmounted by a metal mantelpiece with a photo of 'our Eunice', mum's sister who died of a lung disease the year I was born. A cheap plaster puppy won on the Moor Lane New Year fairground stood alongside the photo trapping some item of clothing hung to dry.

The wooden clothes airer, attached by pulleys and rope to the ceiling and usually in use, directly over the rug and the two upholstered chairs at either end of it made a cosy shrine or grotto of the area round the fire. Dad almost made it a funeral pyre when he set the clothes on the airer on fire whilst carelessly lighting his pipe.

The fire itself like an altar where everyone gathered, needed to be constantly tended and cosseted to get the maximum heat from the poor quality dirty coal. A fireclay brick or two wedged into the hearth reduced the volume of the fire for economy but didn't help the draught needed to keep it glowing brightly. The flickering flames and the hissing of the gases as they were forced out of the small cobs were the entertainment of many a winter evening. The gases, soot and carbon smuts that squirted out of these tiny volcanoes filled the room, the air, our clothes and lungs and caused the constant battle for cleanliness. Nonetheless, it was at these polluting altars that we all worshipped.

|

A proud young mum and her beautiful smiling dark haired daughter who couldn't walk yet. |

|

The tandem with the specially built sidecar for little Joan. |

One reason to keep the room warm was that my sister was disabled and very badly co-ordinated. My home was always a place where Joan occupied one of the two fireside chairs, usually the one facing the window; to give her more to look at but also because it was probably warmer on that side of the fireplace. Throughout her life, my mother tried to keep her occupied with a handicraft of some sort. Every sort of activity that one can associate with girls and women at home have had their place in my childhood. Knitting, sewing, embroidery, cross stitch, weaving, crochet, bobbin work were the staples with ventures, usually unsuccessful, into water colour painting, drawing and writing. All was done on a coarse scale, no delicacy being possible. My sister frequently could take the frustration of her unwilling and clumsy body no longer and screamed and howled violently, thrashing her arms and spindly useless legs about, crashing her supportive boots into the pegged rug over and over and over. She was impervious to all our supplications to think of the neighbours and to pull herself together. Small boys are very unsympathetic to noisy screaming big sisters and I feel shame at some of the things I suggested and did to try and stop these outpourings of desperation by the poor girl. She could be so sweet and loving but infants couldn't be entrusted to this big 'clumsy' and her features became coarse and unwelcoming as a result of an unsuitable diet and lack of exercise. My parents could never be faulted for their care and devotion throughout her life of this poor frustrated girl and woman for whom they could never feel totally lacking in guilt for bringing her into the world. A clumsy mid-wife's forceps appears to have been responsible but in the early thirties working class folks would never consider blaming or suing anyone.

Some of my deepest feelings have been caused by the total anguish on my mother's tear stained face as she watched helplessly as Joan had another outburst of frustration. I later found the photographs of the two of them on a beach in the pre-war sunshine.

The kitchen didn't have a door but led from the back corner of the living room perhaps with a curtain pulled across it in the evenings, a dark narrow whitewashed room with a door to the back yard. A metal framed gas grill for cooking was attached to the wall. In the corner was the copper, a metal boiler built in with a fire hole underneath. It had a wooden lid and a ladling can and a pair of wooden tongs on the top. The clothes were boiled in the copper and taken out with the tongs. On the right as one looked from the living room was the mangle with big white rubber rollers, adjusting wheels and a large handled wheel that turned the cogs and rollers. The whole assembly stood on a cast iron frame over a dolly tub complete with a three legged wooden posser. It was like some torture machine from the middle ages. In practice they were crude but effective machines. My mother's finger end was missing on her right hand, not as you would suppose from an accident during her fifteen years in the cotton mill, but from the ravages of her own mother's mangle. My wife's mother used to sit her on the water catcher at the front of her mangle and trap her dress between the rollers. She knew where she was and she was safe whilst she got on with something. She smeared a little jam on her fingers and gave her a feather. Kept her busy for hours, trying to unstick it. This kitchen outbuilding into our cobbled yard actually had a spare bedroom built over it, but we could not use it as it was unsound and likely to collapse. My mother cannot have been particularly safe whilst working in her kitchen.

The back yard about twenty feet long was almost filled in my memory with a brick and concrete air raid shelter which I can never remember using for its intended purpose. The lavatory was at the end of the yard by the back gate. Surprisingly it flushed but never had the luxury of toilet paper. Torn up newspapers with string through the corner was the norm. Round the toilet was an ash pit which was emptied through a small door in the back street. The walls of the yard were slabs of stone wedged into the ground. I remember climbing up these cliff faces once when one collapsed onto me. How my crushed little finger repaired itself is a miracle but it did, as did the hole in my thigh. As it repaired I scratched at it and my father coming to see why I cried in the night was covered in a spray of fine blood spots. My mother thought he had measles.

Another gruesome story involved me falling on a broken light bulb as a toddler. The wound in my palm wouldn't heal and Dr Savage on Rishton Lane teased out a piece of bulb glass an inch and a half long. The deference to medical men shown by the working people was remarkable apart from the politeness born of necessity as there wasn't any spare brass to pay them.

The George Street house was old, probably just under a hundred years since the cotton mill owners had had it and its neighbours rushed up to house the inflow of cotton operatives and factory hands they needed. Walkers' tannery had been built in the next street in the intervening years and most residents worked in the mill or in the tannery. There seemed to be very little general maintenance during the war and everywhere was dingy apart from the layer of dirt that overlaid my world, from the factory and house chimneys.

Clothes hung out on the back street washing lines were often brought in and out to let the coal men through, but often were dirtier from the chimney smuts than they were when they went out.

There was little traffic and much of what there was horse drawn. The milkman and the green grocer had horse drawn carts as had the chap selling donkey stones and paraffin. Petrol rationing meant there was little recreational driving and the numbers of people owning cars did not include any of my neighbours. There were a few noisy little lorries. There were big wagons carrying cotton bales to the mills from the enormous railway warehouses on Manchester Road and dripping hides from the fellmongers to the tannery. Rag and bone men and peddlers occasionally had a skinny underfed horse but most pushed handcarts as did the knife and scissors grinders shouting their wares and trades round the poor streets. One sharpener however had a cycle set up that, by a clever arrangement of straps, drove a grinding wheel from the pedals.

Most people seemed poorly dressed and clogs and shawls were by no means uncommon. The society we lived in was poor with few possessions. Circumstances in the area were probably unchanged for fifty or more years. Flat caps and mufflers, the epitome of the northern male, really were the norm for working men, not just during the depression. The insurance, rent and club men were usually suited and shod rather than clogged. Many men wore overalls, boiler suits and bib and braces were much more common on the streets. My father used to bring his home in a parcel from the tannery, perhaps they were too mucky and smelly to show. They took a lot of washing, I remember. He was a shadowy figure working all day and Saturday mornings at the stinking tannery. His hands were hard and like leather themselves, he could have hammered nails in with them. I noticed this in particular when he disagreed with me climbing a ladder left against my bedroom window from the back yard. He beat me very infrequently but I certainly remembered that event. His hands didn't soften until he was 80. In the evenings and weekends and on some nights he was a conscientious Air Raid Warden. On rare occasions he would take me for a walk to the allotments on Manchester Road where grand-dad had a bit of land. Once he picked me up and jumped across the Croal. He only just made it and had difficulty hiding his fear at his anxiety. On the allotment I collected some lovely worms and put them in a matchbox. Shrivelled and dead next time I went, it was ages before I realised to my shame that I was responsible.

Grand-dad who also worked at the tannery lived with Grandma on the next street. Grant street really was in the shade of the tannery and Grandma who came from a farming village in Lincolnshire must have felt trapped by that tannery. She had a sparsely furnished house full of stray cats, and an old spaniel called Digo. I distinctly remember her sending Digo to fetch his owner from the allotment on Manchester Road as dinner was ready She never seemed particularly welcoming as did the relatives in Lincolnshire when I eventually met them. This was probably a result of her being ill with cancer for a long time and she didn't survive the war. She took me to see Bambi at the Regal cinema when it was first released. We had a good cry together when Bambi's mother was killed. I still think of her when I hear 'Love is a song that never ends.'

Grand-dad moved in with us until he died in the 1950s. He was a good man and taught himself to make good leather footballs and repair shoes which is what he was doing when his heart packed up. The footballs made me a popular playmate with my peers. 'It's my ball I'll pick the teams.'

He used to sing Music Hall songs and tell of his days near the Bermondsey tannery in London where he was born. Tom Farris was always a keen footballer and when he was too old to play managed some very good local teams in the Sunday leagues. It was a joy to see him in an old photo in the Evening News standing proudly by his league winning team. He once made me a plywood fort for Christmas. It was wonderful. I couldn't believe it was for me. Toys were so few and hard to come by and here I was with a replica fort. He once bought me a fountain pen with a gold nib when I 'passed my scholarship'. I rewarded him by loosing it. I've never forgiven myself. I searched the 'rec', Musgraves' recreation grounds, for hours. I still have an odd feeling on seeing beautiful pens.

My parents especially my mother used to talk about 'before the war' which was a phrase used repeatedly by all. She told me of blue skies and open moorlands walking with friends and relatives. She told me of a popular song I knew called Stormy Weather which came out at a time when the weather was perfect and the sun shone and shone and shone. My mum and dad were in the Clarion cycling club which was politically affiliated to the Labour party and the long rides they went on. The Clarion was my father's life in his teens and early twenties. His cycling stories were a joy to listen to. Such comradeship! The sing songs and get togethers he enjoyed sound wonderful even today.

I looked round at the dirty streets and back yards and tried to picture those rolling hills and the long continuous summer 'before the war', had it been anyone other than my mother that told me of them I wouldn't have believed it. Winter nights were dreadful and the fogs in those days were unbelievable. Those were smelly, choking, persistent real fogs. Vehicles could only show the minimum of lights. There was no street lighting. All lights from shops, factories and housing was masked and hidden. You could buy cardboard disks with a safety pin on the back that were dipped in luminous paint. At least you could see these little blobs of light moving in the blackness. Despite the dark I cannot remember seeing the stars as one should have been able to. Of course I was probably tucked up in bed most of the time. There was so much haze and murk in the atmosphere that the heavens were hidden. Even on sunny days there was a haze in the air and shadows were indistinct.

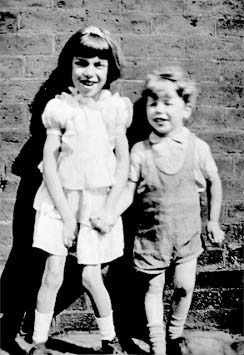

|

War time sunshine with big sister |

The June holidays when the town closed down were by repute the only time you could see across town. I know it as a fact from the 1950s looking out across Bolton from the lofty Scout road at the top of Smithills. All those mill chimneys quiescent. The sound of larks filled my conscientiousness. Did the summer holidays happen during the war? I never had a holiday apart from the breaks from school.

Most Boltonians have mixed feelings about the disappearances of the chimneys. A silent cheer as you saw yet another old giant topple and yet nostalgia for the brightly lit mills and the massive mill engines driving their enormous fly wheels and shafts and pulleys distributing power to all those noisy busy cotton machines. As a child I fished for carp and goldfish in the mill lodges with my cotton, bent pin and worm. Occasionally a pale face would look down from the high windows overlooking the lodge and if we were very lucky give us a wave. The fishing was successful more often than not but we lost the fishes as we tried to land them as, without barbs on our 'hooks', the fish were able to jump off. The fish were put in there by the fairground stall owners who netted them again when the fair next came to town. A friend of mine once caught a big old goldfish which had obviously escaped the net for years. It was a foot long, I assure you. Somehow he managed to get it home but the only place it could go was the bath. I like to think it was returned to the lodge by an angry mother but I really don't know. The lodge itself is now the works yard and car park for EBM on Bentinck Street and was filled in many years ago.

We were taught the fundamentals of the town's main trade at school but I consider myself fortunate not to have been forced to follow my mother and her family into t'mill. She was very skilled at her job and could easily get employment. The only time she could work was in the evenings when dad could take over at home. I remember taking a message to her in the mill at the bottom of the street. The atmosphere was hot, dry and dusty. I couldn't hear myself speak but my mother, having worked from 13 years old, in that environment had no problem and was amused to see me in her work place. She said later that I looked as if I had stumbled onto another planet. I had often been near the entrances when the buzzer had sounded for the end of the working day and the mill workers had poured out like ants from a disturbed nest. They were covered in fluff and dust from the cotton and there was the all pervading smell of the cotton and the hot oil of the machines. A smell that did stay with me was that of a cotton mill fire on Nelson street during the war. The floors of the mill would be saturated with oil from the cotton and the machines and the fire was unstoppable. The cost of the damage was always very great but the profit from the trade must have been equally good as it resumed within months. The history of the town is punctuated with mill fires, especially during the 1800s. It must have been dreadful for the employees to see such a fire in the lean times, of which there were surprisingly many, as their livelihood disappeared with the flames.

A small corner shop facing the burned out mill was the source of a major joy for me. Occasionally they would get a supply of crisps in tin boxes. Three half pence would buy a bag of magic. They seemed to represent those pre-war summer days. There was no chocolate, very few toffees and I often wondered why shops had colourful tin adverts everywhere for Cadbury's this and Fry's this that they never had for sale.

The slot machines that I saw attached to walls never had anything in them. My mother told me I began to walk for the reward of a piece of Cadbury's milk chocolate. She told me this when I had no idea what it was. I felt that I had been born after some catastrophe. Everything seemed to be run down and in decline. Nothing was new. All was making do with what little there was left. I felt like England must have felt after the fall of the Roman Empire and it slipped back to the dark ages. I knew I lived in a dark age.

It wasn't all darkness however because sometimes that darkness would be rent by colour, movement and music. I would only be a spectator but what did that matter. The pictures, those palaces where escape was possible. It seems now that almost everyone went to the pictures at least once a week. The pubs would be the alternative but as a child my knowledge of those was non existent. Hollywood was churning out musicals with the colour and light and sound that were so needed in those days. The British film industry could still make wonderful films, usually black and white, but such brilliant comedies and thrillers and romances. The tone of most films seems to have been very uplifting and moral. Some were sad and nostalgic but most left you with warmth in your heart and a feeling that all was well and the war was just a brief interlude. There were cinemas all over. The town centre ones had the edge for pre-war luxury and were relatively new.

The Odeon, Lido and Capitol were palaces and to be honest I don't think I managed to enter one until I was in my teens. My local was the Ritz on Fletcher street. Bench seats, wooden floors and bare walls were the extent of its furnishings, but the joy I got from those flickering screen images bore no relationship to my surroundings. At the Saturday matinees, Westerns or 'cowwies' were everyboy's favourite and we would gallop along the back street prairies, shooting Indians at every back gate. It was so real I can remember it fifty years later. I remember a film called Danny Boy complete with the Londonderry Air. Such a tear jerker. I mentioned visiting the Regal on Spa Road with Grannie Farris. We saw Jackie Coogan in boyish adventures amongst wide open countrysides and woodlands, all in shades of grey of course. This one had another Irish folk tune as the background music. The Gentle Maiden, which I cannot now hear without a flush of joy welling over me.

Mother used to take me to the Queens, on the fringe of the town centre. She particularly enjoyed the Hollywood musicals. I remember us coming home from Cover Girl singing away to one another when we were almost run over by a lorry being driven too quickly in the blackout with its headlights just thin slits of light like malevolent eyes. It frightened us badly and my mother pulled us against the emergency water supply tank quaking with shock and relief.

Mentioning the Ritz on Fletcher street reminds me of a small eating house or cafe as it would now be called. To stretch our rations a little and because mother would take Joan to a special school at Flash street on certain days, dad would meet me from school on Grecian Crescent and we would eat out. The food was very simple. Shepherds pie and cabbage perhaps would be the main course with a suet pudding for sweet. Children are far less choosy and picky when food is scarce.

My school was a hundred yards from our 'restaurant'. Victoria Methodist was typical I am sure of a working class school of the time. It was strict and poor. Sparsely furnished and only just adequately decorated. The teachers seemed either very old or very young. Children were well behaved, there was no alternative and they were wise enough to appreciate what there was, sparse as it might be. Anything was better than the mean streets most of us lived in. As always the teachers tried their best and most children responded well. I was fortunate and learned easily but a disadvantage was that I exhausted the reading matter fairly quickly and was told to "read them again."

We always seemed to be on a "War Effort" at school, making collections for our brave soldiers. The other services were neglected or thought to have enough perhaps. We collected socks, books, gloves and scarves. We also collected aluminium saucepans presumably for aircraft manufacture. The rewards, for we had to be rewarded, was a copper, bronze or silver coloured cardboard badge. There were gold ones I suppose, but I never saw one. My favourite was the copper badge. We clamoured for any colour or brightness and loved making Christmas decorations with painted paper strips and flour and water paste. Rolls of aluminium foil dropped by aircraft 'chaff', to fool radar. made wonderful decorations, but I think this latter must have been in later years. There was a large room with a sprung floor that needed repair, but funds weren't available and it stood empty and unusable, with paint peeling from the walls and lampshades slipped. This was the sort of state that reinforced in me the feeling of 'sic transit gloria mundae', if that is the right phrase. We had missed out on something good.

One awful event is burned into my memory. I was standing in the school yard looking across at the bus stop opposite. A schoolmate of mine, a girl, had been run over by a bus and men with planks were trying to lift the vehicle to get her body out. Normally children were relatively safe and free to wander, traffic was so light. It was probably this that made us careless, and we were taught 'The Kerb Drill' until it came out of our ears for months afterwards but we didn't really need it after the event we had all witnessed.

A young girl called Sheila Fox went missing in Farnworth and our parents were frightened for a while. I don't think she was ever found. I used to wander all over within a mile or so of home, rarely feeling concerned or anxious. Two lads a year or two older than me kidnapped me on the way home from school. They cut off a strap from my hat and smeared treacle on my face. They frightened me but it was a game to them I suppose. I explored the area simply from curiosity. I climbed into the 'garden' surrounding St Bartholomew's church on our street. There were air raid shelters built there. I was jubilant to find under a dirty coltsfoot leaf a beautifully coloured caterpillar. A tiger in all its glory couldn't have pleased me more. Only the one, surprisingly I never found another.

My mother was worried if I went into town but I still went. It was so easy on the bus. A halfpenny to anywhere it seemed to cost. In these days of motor cars to take the kids half a mile to school we forget that they could walk miles if they tried and survive anything the weather could throw at them. I distinctly remember going to the circus encampment on Queen's park cinder covered football pitch, day after day. I begged them to take me with them when they went. I was six or seven at the time.

In the park itself were black and slimy paddling pools with sloping concrete sides. Totally unhygienic, they must have held every disease from cholera to bubonic plague. We loved splashing around in them, up to our ankles in mud and water up to our knees. My own children liked the clean clear tiled pools that occupied the site twenty years later, but these were judged a health risk and closed down.

At the top of the hill in the park was a colonnaded building which really did feel Greek or Roman. The butterfly house is there now. I don't know what it was. Towards the approach to June 1944 the world was full of Americans with funny accents, chewing gum and chocolate. Girls came from miles around to accompany them walking in the park. I couldn't understand what was going on but I loved those healthy clean well dressed and wealthy young men.

We had lodgers at our little house. People billeted on us. Mostly munitions workers. One came from Newcastle, she was very affectionate but very hard to understand. Apart from the teachers at school all I ever heard were broad Lancashire accents. We had a Polish airman for a while called Boleslaw Bystron, a charming man. He was a very skilled cabinet maker who settled in Bolton after the war and married my mother's friend Ann Robinson. We later had two Americans. It was forty years later that my dad told me they were killed on the D - Day landings. I still have the Indian head five cent piece one of them gave me. We always used to think that all Americans lived in luxury like Fred Astaire or in the Rocky mountains like Roy Rogers. They couldn't have found our cockroach infested house very pleasant. I suppose the warmth the Americans were shown made up for the shortcomings of the accommodation.

Our enforced guests couldn't have been impressed by the shops they saw. There was very little on display. What they did have was sometimes concealed 'under the counter'. There were no lights of course but what there were were queues. Queues for everything. "If you see a queue outside the Co-op", said my mother, "Join it. Find out what it is for later". But there was no money for frills, even though there were no frills to buy.

Clothes were rationed and furniture was basic and cheap. Surprisingly some lasted well and is still in use. There was a symbol, a stylised CC41, for this 'utility' produce with which we became familiar. Most did with peg rugs and knitted clothes. Even socks were knitted and reknitted. Heels and elbows were darned. There was no room for pride. I remember having knitted swimming trunks which 'collapsed' when they got wet. If one dared to dive, one resurfaced knickerless.

The swimming baths seemed to keep going together with the public 'slipper' baths which accompanied them. The sexes were segregated when swimming, but you did hear talk of brazen 'mixed' bathing. I loved the baths, Bridgeman Street and High Street, even though the water was heavily chlorinated. I couldn't swim but, hanging on to my knitted trunks, would jump into the ten foot end, hoping that when I surfaced I would be near enough to grab the rail or steps. I did this even off the diving boards. Well, I'd seen Johnny Weismuller at the pictures and he never let the water or crocodiles frighten him. It only took a couple of near misses on surfacing and my frantic grabbing and kicking for the side and I was swimming. I never told my mum of course. Reading through some of this I wonder how I survived.

There were machines on the walls of the swimming baths which dispensed a little squirt of hair cream. The RAF were known as Brylcreem boys. They were thought by some to be having relatively safe military service, the ground crews in the UK that is. This didn't apply to my mother's brother Uncle Charles, aircrew Sergeant, stationed on the Isle of Man. After Gran's death, he and and his young wife Hilda moved into the Grant Street house. Selfishly I remember cousin Charles as he owned a three wheel bike and I was bigger than him.

The Royal Air Force took over the technical college on Manchester road for training technicians and there were mock ups of aircraft at the back. There were always displays on the Town Hall square to raise funds for aircraft or tanks or submarines. The War dominated everything and it was probably the 1950's before I realised there were other things. Even then National Service was still in effect and my RAF service was influenced by all my childhood memories of the war. Adults talked of little else and the newspapers were filled with news of the various campaigns, routs, attacks, sinkings, and bombings. The children of Northern Ireland must have a similar mentality but perhaps their feelings aren't as clear cut as ours were. At least we were all on the same side.

In the minds of older folks such as my grandparents war must have felt quite normal, in that they had grown up or been in the first Great war and then their children were now in the second. My granddad talked of his brother, Uncle Frank, who was killed on the Somme, in exactly the same way that mother talked about her Uncle Chris who was killed at Dunkirk. To me it was all the same war. I used to play with Chris's daughter, Margaret, who was my age but who couldn't remember her dad.

People still talk about the camaraderie that adversity engenders in people. There was much more sharing of resources. The street life was richer with people exchanging bits of gossip and information of where bargains could be had or scarce items bought. There was much more social life in the movement of people from place to place. Relatives were concerned about the forces and the war effort. The insularity of families nowadays has meant a definite loss to society. There are many benefits to universal car ownership and blanket watching of TV by all, but a thriving community spirit isn't one of them.

The TV soaps are a substitute for the real neighbourhood activities that older people knew in pre TV days. Far safer and more secure behind your closed and locked front door but lacking in the flames and sparkle of reality that could have singed onlookers in the past.

We had our mass media even then. I'm thinking of the papers and the wireless. The wireless seemed so important and such a strong influence on the feelings of everyone. It was a link, a lifeline to the general national consciousness. When doors were forced to close during the winter and at night it became the upholder of spirits, the morale booster when everything felt hopeless. No cats' whiskers for us, ours was a proper battery and accumulator job. Of course there was the news and announcements about the war, but overall there was music and mirth and happiness. There were plays and pastimes to distract the mind from the darkness of the time. The humour was simple and vigorous. It appealed to us all. There was drum banging, flag waving, speech making and cheering but mostly there was a striving away from the hard reality of war. The propaganda, if that was what it was, was to maintain the peaceful mainstream of British life.

The big bands like Glenn Miller, Joe Loss, Henry Hall and the singers Bing Crosby, Vera Lynn, George Formby and the youthful Sinatra emphasised the romance, the nostalgia and the humour of the forces. People used to whistle and sing when I was a lad and it was the wireless that made them do it.

It wasn't all black. When people got together they made the most of it. Life was a laugh, to be enjoyed and savoured not worried about. Christmas time was enjoyed despite the shortages of everything. The ingenuity of some cooks was unbelievable and they would start putting by in October for that little bit extra at Christmas. Granddad's brother Charlie was on naval convoys to Russia at the end of the first war and somehow Joan and I had an enormous stocking from that time. I got as much pleasure from the contents of that stocking, right down to the orange in the toe, as any modern child with his room-full of presents.

After the feasting, it was show time. The guests did their party pieces. My mother's friend Ann was a wonderful performer. She could sing, play the piano and orate like a professional. "Waterloo" an epic poem was one of my favourites. She also did a poem about the "vind blowing down the front of the back of my house, not the devil the veend". It sounds pathetic but it was magic. My mother did a lisping story of a trip to "the animal fair, the birdth and the beasth were there". She could never not say a dialect poem called "Ar Murry's bonnit" and get away with it. I can't remember what dad did. Simple pleasures really were the best. I remember last New Year's Eve when we sat and watched someone on the tele do our party pieces for us without us lifting a voice or a finger. People will live their lives and never know that they have some talent to entertain.

My grandma Farris from Lincolnshire had a younger brother called George and on rare but delightfully welcome occasions he would appear on the doorstep from that world of fields, trees and sunshine still existing somewhere. His small suitcase would hold eggs, fresh fruit and the occasional sweet. Smiths the crisps makers seemed to own half of his county and the other half was made of runways for bombers. I loved this fine man with his strange accent and humour bubbling under his every statement. His arrival lifted our spirits above any depression we may have felt. The stories he told put the world back into perspective and made my parents believe that the good times would come back someday.

More locally, relatives and friends used to call on one another, usually for Sunday tea and we used to go to Annie Lamb's on Leonard street. We always walked with dad pushing Joan's pram. Cousin Enid always wanted to play at doctors and Dorothy her sister eventually became one. I remember a particular salad tea because there was real Heinz salad cream on the lettuce and it was followed by custard and pineapple chunks which were the result of a surprise queue at the Co-op. They had a tiny ginger kitten which fell in the custard. It carried the event in its fur for weeks. One summer Sunday I remember hearing "People will say we're in love" on someone's wireless as we walked home. It was beautiful.

As did most townies, we had a Co-op in our street. It was a big part of my early childhood. The smells were wonderful and the way things were packaged and sold. Check books and check slips and dividends were the order of the day. Most of our food came from there. As did most other things come to think of it.

Cradle to grave was or should have been the motto. The Co-op did and sold everything. Tailors, furnishers, funeral directors, entertainment, insurance, butchers. The co-op was almost a religion. It had so many outlets, shops, halls, branches the country could have been the United Co-opdom. It still exists today because of its sheer size and mass in earlier decades. It is a dinosaur that avoided the meteorite.

Every so often mother had a break and spent the Sunday with her family at Middleton Junction. She took me with her sometimes. We set off very early to catch the first number 8 bus to Manchester and then from Cannon Street, the 59 to Chadderton. Half the day was spent travelling there and back. It seemed like another country and another life it was so far away. I sang "I'll be seeing you" to the front upstairs bus window as I gazed out. The whole bus gave me a round of applause when I finished or maybe because I finished. Folks had simple tastes in those days. The journey takes about twenty minutes today on the M62.

Grandma Rigby was a sweet soul. She had been baptised a Roman catholic but had married my Church of England grandfather in the parish church in Bolton on New Year's day 1907. They had moved to Middleton Junction as grand-dad was a valued high counts or fine counts spinner and able to earn a good wage at the new mill he went to. Grandma's change of religion and pregnancy didn't hinder the move either.

It was easy to be honest and religious in the war. There was nowt to pinch apart from the fact that mother would never have forgiven me. Truth, bravery, valour, selflessness, wasn't everybody so in wartime?! Another memorable event was connected with the church. On the Sunday following the war's end in the summer of 1945, I was standing on the tower steps inside St Mark's church on Fletcher street. The church was full to capacity, hence my position, and every single one was singing Jerusalem as though their lives depended on it. I have rarely been so moved in the almost fifty years that have elapsed since.

The end of the war was almost a signal for the start of a new lifestyle for me. We had the street parties and celebrations to welcome the homecoming men. Neighbours that I had never seen. Some of my childhood friends had to get used to a privileged stranger living with them as their daddies returned. It is hard for younger people to accept that although the war was over there was still a shortage of goods in the shops. Food was still rationed as was most other things. The heroes didn't feel that they were being treated as such and life was darker and drabber than it had been six years earlier. At least it was over. No more long absences from their loved ones and anxieties that they may not meet again. 'Never again' was the phrase on their lips, as they tried to pick up the pieces.

|

Street trip to Southport - Bert Coop |

For us life continued as before. There wasn't a sudden change and it was a while before I realised that the evenings were no longer black after sunset. The gas lamp at the street corner a few yards from our front door was just a piece of cast iron play equipment until one evening a chap with a ladder came, fitted a mantle and switched it on. About this time I saw a neon sign come back to life on Trinity Street. A simple little red snake of letters was pure magic for me although I can't remember what it said. It may have been the Queens cinema.

The films were still all of warfare and heroism. I suppose there was a backlog of these still coming through the pipeline and John Wayne and Errol Flynn would be fighting Japs on Pacific islands for years to come. There were exceptions such as Meet me in St Louis and Walt Disney's cartoon films, but many producers couldn't shake off the military themes and the post war traumas in war torn Europe.

We lived within a stone's throw of Burnden Park, just across the railway and I seem to remember the dreadful day when after early cheers the ground was unusually quiet. As older boys and men returned quietly along the street we heard of the dreadful disaster that had happened when crush barriers had collapsed on the embankment. Many were killed and injured. Before I managed to go to watch the Wanderers, my parents had decided to move back up Chorley Old Road where they had lived during their newly wed pre-war years. Life was to be different.

We moved in November 1946, the war having ended well over a year previously although it was hard to tell in many ways. Some street lights were back on and we had a gas lamp just outside our wonderful new house, built just before the war. The ground floor of the house was divided into two. The front part was an entrance 'hall' leading up the stairs with a door to a living room with a tiled fireplace. There was a door in this room to a dark cupboard under the stairs which was the pantry. There was a tiny window at the back of the pantry but little light entered as it led into the entry or ginnel between our house and our neighbours'. This passage, which was very dark in November, also had a door to another cupboard under the stairs which was our coal hole.

The back part of the ground floor had a lavatory 'inside the house' but unlit and having to be entered from outside the house. There was a tiny kitchen with a sink and gas cooker and a passage that passed behind the lavatory to a room made wonderful by an enamelled cast iron bath and a wash basin, both even had two taps. It took weeks to accept that hot water ran from one of them.

I shared the largest of the three modest bedrooms with grand-dad. There was a small fireplace in one wall but I can't recall ever seeing a fire in it. Pots under the brass bedsteaded beds, a wardrobe, a dressing table with a pivotted mirror and a chest of drawers were the furniture inventory. When the small engineering firm moved out of the factory opposite and Lonsdales the bakers moved in the bedroom was always full of the smell of bread baking and the noise of the slicer and wrapping machinery.

I was immediately struck by how much colder the winter was at the dizzying heights of Sofa Street. More than enough snow for sledging down the cobbled lower section of the street at the side of Musgraves mill. Grand-dad the fort builder turned his skills to sledge making and although his handiwork turned out to be too big and heavy especially for pulling back up the hill it was shortly to be very useful . That winter of 1946 - 47 was indeed a hard one and to add to it the miners went on strike. We learned that fuel was to be had in the form of cheap coke at the gas works down town provided the buyer was prepared to collect. It could be collected and the bag carried on a strong back or a bike through the snow but what a job it was. However a lad who was nearly nine after all with an oversize sledge could pull a bag home to keep his disabled sister warm. What a hero! My mam was so proud of her lad. She found me an old moleskin fur coat which I wasn't too proud to wear. I even discovered it kept me warmer worn inside out. It really was a cold winter. They still show photographs of it with trams stuck in the snow unable to move, or was that 1941? Another aspect I remember was that folks used to rally round and clear footpaths and shopfronts to help people get about. I suppose that after the years just passed there was still a lot of community spirit about.A new school, a new community and new friends are specially hard when one is a child but you don't question the circumstances but try and make the most of it. The residents of council estates were to my mind different in their self opinion at that time. Of course there were class boundaries and people you touched your hat to if only figuratively, but as a general rule working folks were decent, hard working and respectable. They tried to better themselves but the gaps between them were not large and they didn't condemn the less fortunates. Most rented their homes and council property was modern, usually with 'mod cons' and a modest garden. Our neighbours made us welcome and invited us to join any communal activity. My grandfather and to some extent dad too had allotments behind our back fence all the time they lived there. Dad loved his garden and his greenhouse, growing annuals in the former, tomatoes and chrysanthemums in the latter. As the house was so small it was a good way to get out for a while.

Several of our neighbours were Roman Catholics as had been the house's previous tenants and I went on several coach outings to monasteries, holy wells and churches. It was all the same religeon to me and I enjoyed it. I soon learned to make the correct responses when I was questioned or blessed. I was a streetwise child of the war.

I still sang reasonably well and my new headmaster, Mr Pendlebury recruited me to sing in the Parish Church choir down town, where we were actually paid to sing. I still go to the same church to help ring the bells on Sunday mornings and remember those journeys so long ago. Town is so quiet now on most days.

I had a friend called Norman Farrell who lived up the street and who was a natural historian, he was all of ten years old. He knew every bird including its song and what colour its eggs were; where to find the nests, take the eggs and how to puncture and blow the contents out. That was the way one studied birds. No wonder their numbers decreased so rapidly. He was nonetheless a great companion and it is as a direct result of his influence that I became a biologist and a lover of the great outdoors. My children especially the boys became mountaineers and world travellers as a result. Collectively we have much to thank Norman for. His sister Mary had a big wedding anniversary event last year and I wrote congratulating her and asking for Norman's address. After delaying my thanks to him for more than fifty years it was sad to hear he died last year and was never able to receive them.

Springtime followed that awful winter and I was eventually introduced to the big beautiful moorlands over Bolton away from the mills, the noise and the bustle. We, Norman and I, went on the last trams along Chorley New Road to Lever Park at Horwich and up the mountainous Pike at Rivington. We walked from home through the park at Moss Bank and Barrow Bridge up to Winter Hill, mastless then of course. We saw a kingfisher and heard the skylarks. It was still possible to clearly see the remains of cottages and buildings where communities had dwelt right up on the tops of the moors by Sugarloaf Hill and Burnt Edge. We met some geology students from Manchester University who showed us the ripples on the sandstones making up the walls. We couldn't believe their stories of ancient seas especially up on Winter Hill. They held my hand as I leant out over a mine shaft and I dropped stones for them to time the drop and work out how deep it was. Fearless then, I quake at the thought of it even now.

|